| Meet the Editorial Team |

| Where We Are Now... |

| The Editorial Process |

| Project Publications |

| Key Ideas & Theories |

| Google Analytics Reports |

The Editorial Process

There are nearly 5000 Schreiner letters, located in sixteen archives on three continents.

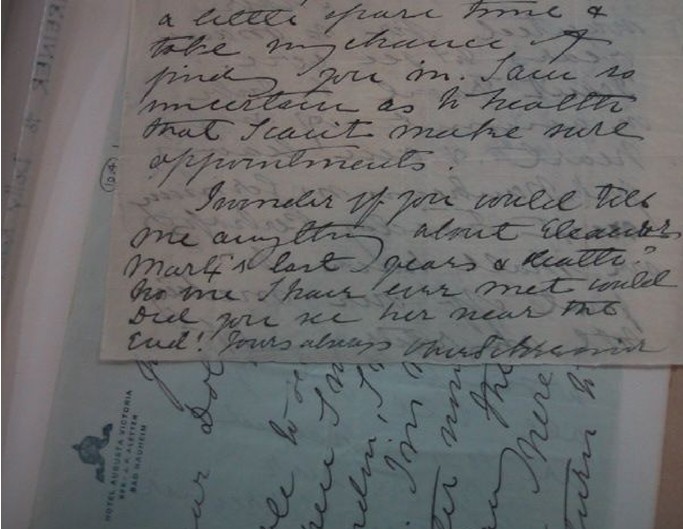

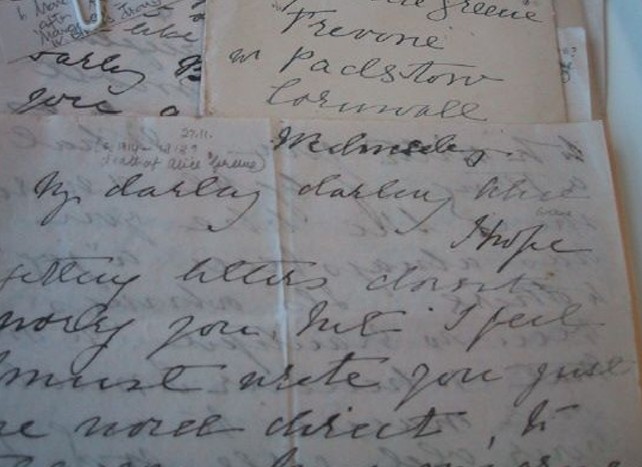

They look like these two examples - but there are thousands more of them, many of them are long - and most of them are much more difficult to read than these examples.

We started our work by sitting in the archives concerned and transcribing Schreiner’s letters, postcards, telegrams, notes and so on - and this has meant transcribing every insertion, deletion, omission, mistake. Then we checked this once, twice, to make sure our transcriptions are as accurate as possible. Then, some weeks or months later, another researcher went to the archive in question to check the transcriptions against the originals and then edit any mistakes made by the person who first transcribed them. What results can be seen below

This shows ‘Mark-up’ turned on in Word, in order to show the number of transcribing errors spotted by the checker: being very very accurate regarding the ‘bird in flight’ aspects of how letters are written is surprisingly difficult, and it needs pains-taking attention to the detail. But this is the start, and not the end, of what we have done to prepare our transcriptions for research and analysis - and also publication - purposes.

The next stage has been to ensure there is fully accurate consistent ‘meta-data’ for each letter, postcard and so on - this is the basic information for working with the letters ‘as data’ using computer-assisted methods of ‘managing’ them all as a data-set, and also for analysing them. An example of the ‘meta-data’ is shown below.

CLASSIFYING INFORMATION

Letter date [20 April 1899]

Address from [2 Primrose Terrace, Berea, Johannesburg]

Address to [Lyndall, Newlands, Cape Town]

Who to [William Philip (‘Will’, ‘WP’) Schreiner]

EDITED COLLECTION

Editor [Rive 1987: 348-9]

ARCHIVE COLLECTION REFERENCE

Archive name [University of Cape Town, Manuscripts & Archives, Cape Town]

Archive ref [Olive Schreiner BC16/Box2/Fold1/Jan-June1899/16]

We also then wrote notations for many of the letters. These come in two varieties. One is what is referred to on many Schreiner’s letters as ‘Legend’. These are a bit like Footnotes, but with a different philosophy concerning editorial information-giving, because they are mainly concerned with explaining uncertainties and oddities in the meta-data. The second kind is akin to Footnotes and referred to as ‘Notations’; these mainly provide information about references to Schreiner’s unpublished or published writings contained in the letter:

[LEGEND: The date is derived from the postmark on an attached envelope, which also provides the address this letter was sent to..]

[NOTATION: The ‘Bushman paper’ refers to one of Schreiner’s ‘Returned South African’ essays, now in Thoughts on South Africa; ‘The Boer Woman’ also appears in the same posthumous collection.]

But the process doesn’t stop here!

In order to be able to analyse the letters within a project research tool called a ‘Virtual Research Environment’ or VRE, the transcripts and Notations have to be prepared in what is called an XML format - this is a way of computer coding, for example, underlining, deletions, paragraphing & so on. And because of the way the kind of XML we use has been developed, it is ‘future-proofed’, enabling letters to be shown in successive versions of HTML (HyperText Markup Language) and so seen ‘as letters’ are meant to look, via a web-browser.

So - XML is a set of rules for encoding text-based documents electronically and a textual data format frequently used as a basic language that can be converted into HTML. HTML is the most common markup language used for writing and preparing webpages. And ‘jEdit’ is used as an XML processor (that is, we write our xml using jEdit) and it involves a number of complexities, including ‘tagging’, for example to indicate whether something is a letter, a postcard, a telegram and so on.

An example of XML applied to the content of a letter is show below:

In working in XML, ‘tags’ have to be carefully defined; putting them in by using jEdit is time-consuming - but they are project-defined and developed and aid the analytic and publishing processes. The XML tagged versions of the letters are very hard to work on analytically - what results doesn’t look like letters at all because bristling with codes - but XML is easily converted into HTML, which in a web-browser looks like MS Word. However, one upside is that XML files are small compared with MS Word and resist corruption. Also, while jEdit is unforgiving to use, it does enforce the ‘well-formedness’ of letters by showing up errors, something which it is very important that we as editors and researchers should know about as soon as possible.

What these technicalities are for is to enable the letters to be published and searched electronically - and also to support our ‘behind the scenes’ detailed research on the Schreiner letters. Working with c4800 letters, ranging from 300 or 400 words to sometimes thirty or so densely written pages, is not easy in itself. However, analysing this number of letters, and letters of such size and magnitude, is even less easy.

Large-scale datasets (c4800 ‘cases’ is large-scale in anyone’s terms) are often analysed using a ‘social science standard’ commercial package called SPSS - but this is designed to analyse very simple information (yes, no; age 30-39; single, partnered, etc) for a lot of cases, and not immensely detailed ones like the Schreiner letters. The analysis of qualitative text-based datasets often makes use of CAQDAS (computer assisted qualitative data analysis software) packages - but c4800 cases, many of them a huge size, and containing different ‘genres’ of data, is beyond their capacity. The Schreiner letters are too many and too large.

At basis, we transcribe and xml the Schreiner letters, then, so that we can design our own project-specific analytical tools for analysing a very large, but also qualitative, dataset; and also so that they can be published and read online. This first involves our ‘Virtual Research Environment’ or VRE, and the second the ‘User Interface’.

The Virtual Research Environment or VRE is a kind of project management piece of custom-designed software produced by the Humanities Research Institute Online technical staff who have worked with us on the Schreiner Letters Project. The VRE provides us with four essential things without which we would have drowned in the immense amount of written material we have been working with:

- Data packaging - the VRE helps us work with the letters as ‘a set’ from contents which are both very large in number, and also internally diverse.

- Data organisation - the VRE constrains us to devise basic organisational principles (around the collection, the archive, the date).

- Data identification & retrieval - the VRE enables search & find on both ‘meta-data headings’ and also the full-text of all the Schreiner letters.

- Computer-assisted analytical tools - the VRE helps us to work with the letters and whole letters, rather than plunging in to producing the hierarchical linked indexing of contents which is constrained if not determined by most CAQDAS ‘off the peg’ software packages.

The slightly strange phrase, the ‘User Interface’, refers to one of the most important products of our work on the Schreiner letter transcriptions. This covers all the webpages, search facilities, editorial information, that surrounds the Schreiner Letters Online. Generating HTML or web-browser readable versions of our transcriptions is crucial to aid and support our research work - and it also enables electronic publication in a form in which readers can access and read the Schreiner letters.

As well as wanting to ‘just read’ the letters, readers face the same kind of issues that we editors have done in researching such a very large number of letters - where do you start? how can it be made manageable? how can you find out the things you’ll be particularly interested in? what other important aspects are there that you’ve never thought about but might be interested in? The role of the User Interface is to support readers in asking - and answering - these questions and related ones that occur to them. The user interface provides a high level of sophisticated ‘search and find’ tools, enabling readers of Olive Schreiner’s letters to navigate their own routes through them.